The use of synthetic amino acids (AA) in diets for pigs has increased in the past few decades due to increased availability and reduced prices of these AA. The increased use of synthetic AA has caused a reduced need for inclusion of soybean meal (SBM) in diets. For instance, a common grower pig diet without synthetic AA needs around 35% SBM to full fill the requirements for all indispensable AA, but a diet with 5 synthetic AA only requires 17% SBM. It has generally been assumed that pigs fed diets containing synthetic AA will have growth performance, protein deposition, and carcass quality that is no different from that of pigs fed diets based in which the majority of the AA are furnished by SBM as long as the requirements for all digestible AA are met. It has also been assumed that diets formulated with large amounts of synthetic AA, compared with diets based on SBM provide more net energy to pigs because these diets contain more corn and less SBM. However, some of these assumptions are not based on strong scientific evidence, and results of recent research has raised doubts about previously assumed effects of using synthetic AA. Therefore, the objective of this experiment was to test the hypothesis that the use of synthetic AA instead of some of the intact protein from SBM does not impact growth performance, carcass composition, energy deposition, blood cytokines or abundance of intestinal amino acid transporters when fed to growing pigs.

Experimental design

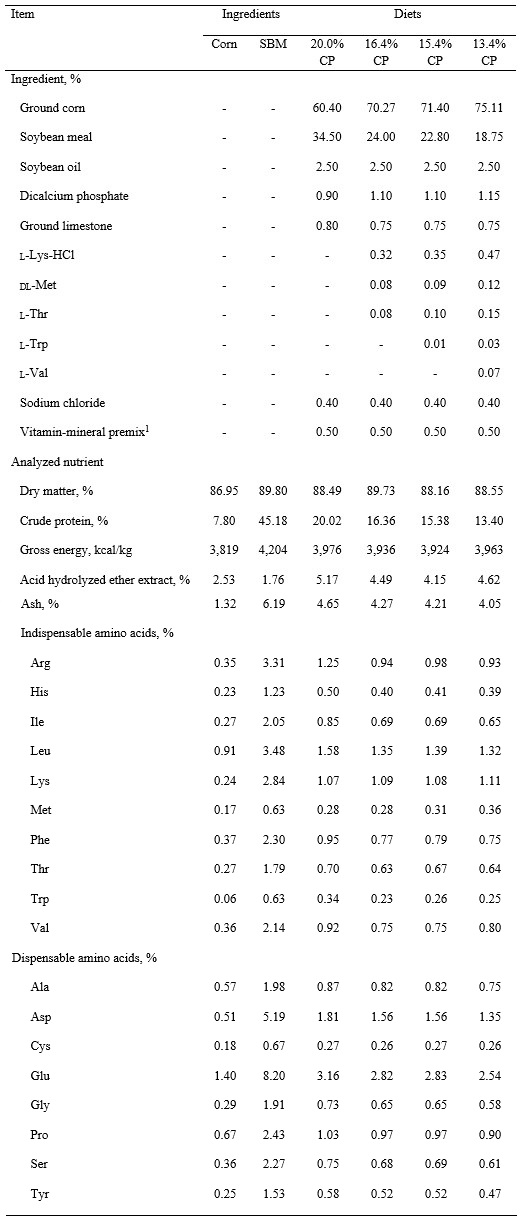

A control diet was formulated based on corn and SBM without synthetic AA (Table 1). Three additional diets were formulated by reducing the inclusion rate of SBM and adding 3 synthetic AA (i.e., Lys, Met, Thr); 4 synthetic AA (i.e., Lys, Met, Thr, Trp); or 5 synthetic AA (i.e., Lys, Met, Thr, Trp, Val) to the diet. Therefore, a total of four diets were used. Concentrations of standardized ileal digestible indispensable AA were at or above requirements for growing pigs (NRC, 2012) in all diets, but the concentration of crude protein (CP) was reduced from 20.0% to 16.4, 15.4, or 13.4% by including 3, 4, or 5 synthetic AA in the diets.

Animals, housing, feeding and sample collection

A total of 176 growing pigs (average initial body weight = 32.2 ± 4.2 kg) were allotted to the four diets using a randomized complete block design. Sixteen pigs were randomly selected at the beginning of the experiment. These pigs were euthanized and carcass composition was determined. The remaining 160 pigs were randomly allotted to the four treatments with four pigs per pen (two gilts and two barrows) and 10 replicate pens per diet. Diets were provided to pigs on an ad libitum basis for 28 d. Individual pig weights were recorded at the beginning of the experiment and at the conclusion of the experiment on day 29. Data were summarized to calculate average daily feed intake (ADFI), average daily gain (ADG), and gain:feed ratio (G:F) within each pen and treatment group.

At the conclusion of the experiment, one pig per pen was selected based on body weight and sex. Two blood samples from this pig were collected in heparinized or EDTA-containing vacutainers. The pig was then euthanized via electric stunning and exsanguination. Carcasses were processed to record weights of full and empty viscera, hot carcass weight, dressing percentage, and chilled carcass weight. Body composition was determined by partitioning the carcass into carcass, blood, and viscera components. Jejunal and ileal tissues were also collected, fixed, and analyzed for villus height and crypt depth. Ileal mucosa samples were analyzed for AA transporter gene expression via qRT-PCR. Digesta samples from the intestines and colon were collected for ammonia and protein concentration analysis. Muscle, fat, skin, blood, and viscera samples were stored, lyophilized, and analyzed for protein, fat, and energy content.

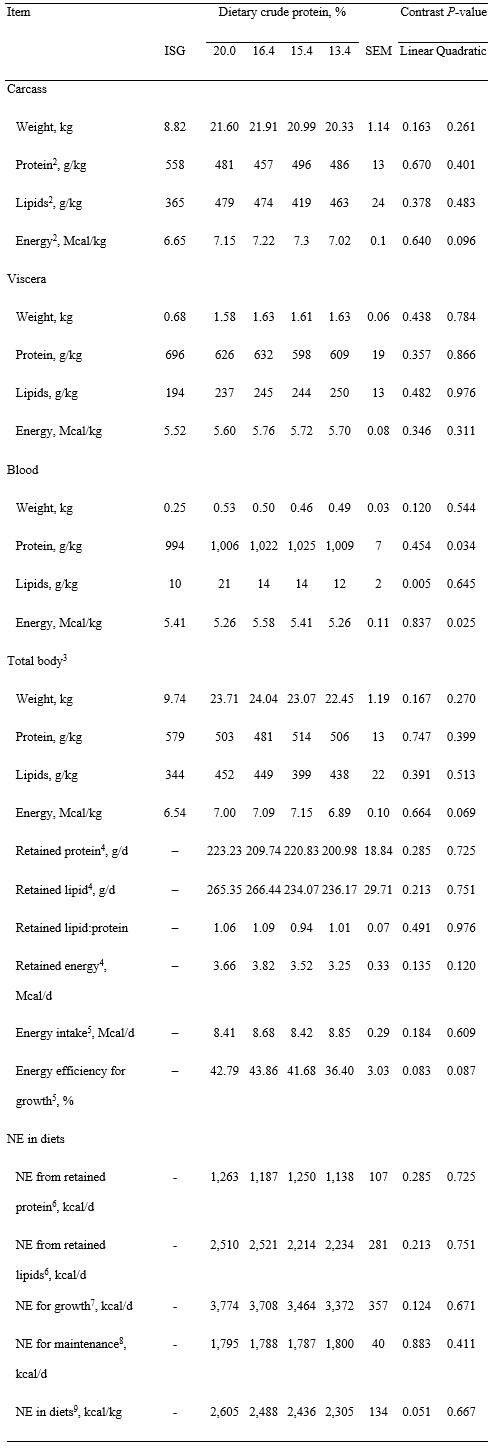

Freeze-dried samples of blood, viscera, muscle, fat, and skin were analyzed for dry matter (DM), protein, fat, and energy to estimate total nutrient concentrations in the carcass and viscera. Total energy, protein, and lipid content in each pig were calculated by summing their contributions from blood, viscera, and carcass on a DM basis. Retention of energy, protein, and fat during the experimental period was determined by comparing the values in treatment pigs to the group of pigs that were slaughtered at the beginning of the experiment. Net energy for growth was calculated from retained protein and lipids, while net energy for maintenance was based on metabolic body weight. Energy efficiency for growth was derived by dividing retained energy by daily energy intake and expressing it as a percentage.

Data were analyzed using a mixed model, with diet as the fixed effect and block as the random effect. Linear and quadratic effects of dietary protein reduction were assessed, and statistical significance and tendencies were considered at P < 0.05 and 0.05 ≤ P < 0.10, respectively.

Results

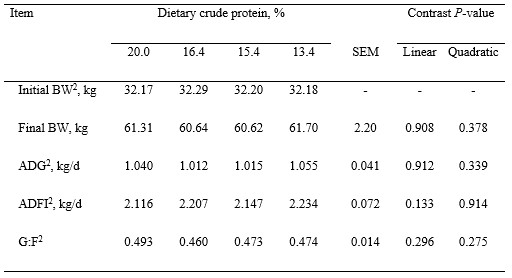

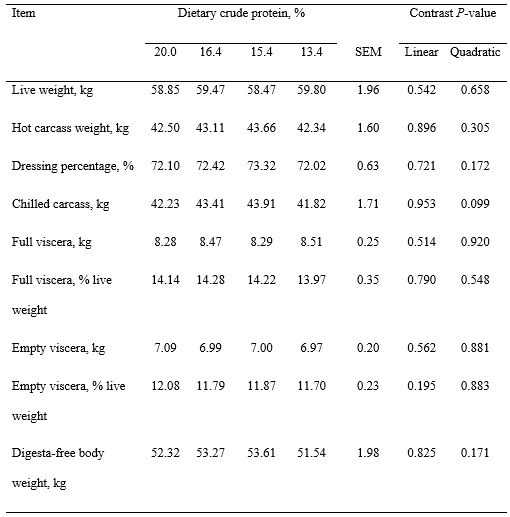

Pigs remained healthy during the experiment and no mortality was observed. Final BW of pigs was not affected by dietary treatment (Table 2). Average daily gain and ADFI of pigs were not affected by reducing SBM and increasing synthetic AA in diets, which resulted in no differences in G:F. Live weight, hot carcass weight, dressing percentage, viscera weights, and digesta-free weight were also not different among treatments (Table 3). However, the weights of chilled carcasses tended to decrease quadratically (P = 0.099) as dietary protein was reduced, but weights of carcass, viscera, and blood were not affected by dietary treatments (Table 4). Concentrations of protein and fat in carcass and viscera were not affected by dietary treatments, but concentration of energy in carcass, blood, and bone-free total body tended (quadratic, P < 0.10) to increase and then decrease as dietary protein was reduced. Retained protein, lipid, and energy were not affected by dietary treatment, but energy efficiency tended (quadratic, P = 0.083) to decrease as dietary protein was reduced.

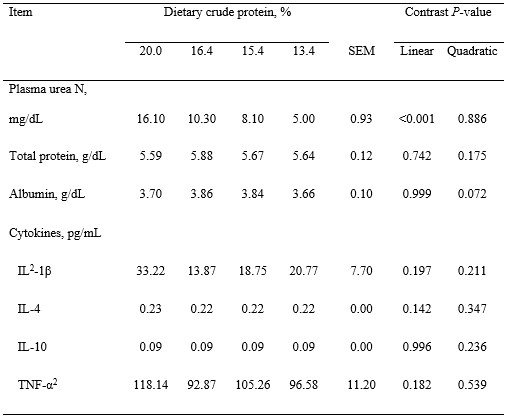

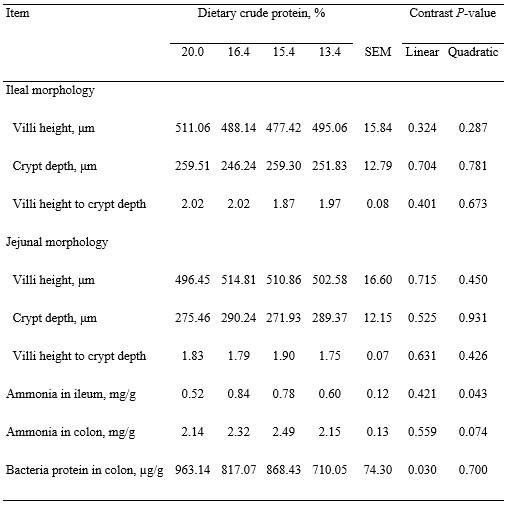

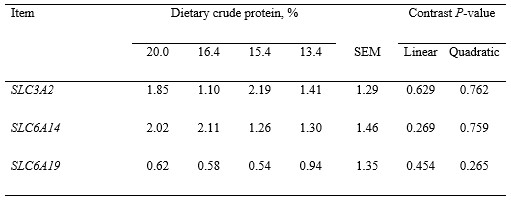

Plasma urea N was reduced (linear, P < 0.001) as dietary protein was reduced, but blood total protein was not affected by dietary treatment (Table 5). Albumin in blood tended (quadratic, P < 0.1) to increase and then decrease as dietary protein was reduced, but concentrations of cytokines were not affected by dietary protein. Ileal and jejunal morphologies were also not affected by dietary protein (Table 6). Ammonia concentrations in ileal digesta increased and then decreased (quadratic, P < 0.05) and ammonia in colon digesta tended (quadratic, P < 0.1) to increase and then decrease as dietary protein was reduced. Bacterial protein in colon digesta was reduced (linear, P < 0.05) as dietary protein was reduced, but abundance of genes related to AA transporters in the ileal mucosa were not affected by dietary protein (Table 7).

Key points

- Reducing SBM inclusion while supplementing with synthetic AA in diets did not affect growth performance or carcass composition

- Reducing SBM inclusion while supplementing with synthetic AA in diets did not affect protein or fat deposition but may affect energy efficiency for growth

- Reducing SBM inclusion while supplementing with synthetic AA in diets did not affect abundance of AA transporters, villi height or crypt depth of jejunum or ileum, or blood cytokines

- The NE in SBM is greater than reported by NRC

Appreciation

Funding for this research from the United Soybean Board (St. Louis, MO) is greatly appreciated.

Table 1. Ingredient composition of experimental diets and nutrient composition of ingredient and experimental diets, as-is basis

1The vitamin-mineral premix provided the following quantities of vitamins and micro-minerals per kilogram of complete diet: Vitamin A as retinyl acetate, 11,150 IU; vitamin D3 as cholecalciferol, 2,210 IU; vitamin E as DL-alpha tocopheryl acetate, 66 IU; vitamin K as menadione nicotinamide bisulfate, 1.42 mg; thiamin as thiamine mononitrate, 1.10 mg; riboflavin, 6.59 mg; pyridoxine as pyridoxine hydrochloride, 1.00 mg; vitamin B12, 0.03 mg; D-pantothenic acid as D-calcium pantothenate, 23.6 mg; niacin, 44.1 mg; folic acid, 1.59 mg; biotin, 0.44 mg; Cu, 20 mg as copper chloride; Fe, 125 mg as iron sulfate; I, 1.26 mg as ethylenediamine dihydriodide; Mn, 60.2 mg as manganese hydroxychloride; Se, 0.30 mg as sodium selenite and selenium yeast; and Zn, 125.1 mg as zinc hydroxychloride.

Table 2. Growth performance of growing pigs fed experimental diets1

1Least squares means represent 10 observations per dietary treatment.

2BW = body weight; ADG = average daily gain; ADFI = average daily feed intake; G:F = gain to feed ratio.

Table 3. Weights of carcass and viscera of pigs fed experimental diets1

1Least squares means represent 10 observations per each dietary treatment except that means for dressing percentage and empty viscera of diet containing 15.4% protein represent 9 observations and that means for dressing percentage and full viscera of diet containing 13.4% protein represent 9 observations.

2Digesta-free weight was calculated as the sum of the weights of chilled carcass, empty viscera, and blood.

Table 4. Analyzed composition of bone-free carcass, retention of energy, protein, and lipids in growing pigs fed experimental diets, and net energy in experimental diets1, dry matter basis

1Least squares means represent 10 observations per each dietary treatment.

2Concentrations of protein, lipid, and energy represent analyzed N × 6.25, acid hydrolyzed ether extract, and gross energy in each body part, respectively.

3Total body referred to the sum of carcass, empty viscera, and blood and bones were not included in the analysis and calculations.

4Retained nutrients and energy in the body were calculated using the difference in body composition between reference group of pigs (n = 16) and body composition of pigs fed experimental diets for 28 d.

5Energy intake was calculated as multiplying average daily feed intake of pigs by analyzed gross energy in respective diets; energy efficiency for growth was calculated as dividing retained energy by the energy intake and multiplying them by 100.

6NE in protein and lipids was calculated by multiplying retained protein and lipids by 5.66 and 9.46 kcal/g, respectively.

7NE for growth was calculated as the sum of NE from retained protein and lipids.

8Daily NE for maintenance was calculated by multiplying the mean metabolic body weight (kg0.60) by 179 kcal (Noblet et al., 1994).

9NE in diets was calculated by dividing the sum of NE for growth and NE for maintenance by daily feed intake.

Table 5. Concentrations of plasma urea N, total protein, albumin, and cytokines in plasma of pigs fed experimental diets1

1Least squares means represent 10 observations per each dietary treatment except that means for IL-1β of diet containing 20.0% protein represent 9 observations and that means for IL-1β and TNF-α of diet containing 16.4% protein represent 9 observations.

2IL = interleukin; TNF = tumor necrosis factor alpha

Table 6. Morphology of jejunal and ileal tissues and ammonia concentrations in ileal and colon digesta and bacteria in colon digesta of pigs fed experimental diets1

1Least squares means represent 10 observations per each dietary treatment except that means for ileal morphology of pigs fed diet containing 15.4% protein represent 9 observations and that means for jejunal morphology of pigs fed diet containing 13.4% protein represent 9 observations.

Table 7. Abundance of genes for amino acid transporters in the ileal mucosa of pigs fed experimental diets1,2

1Data are least squares means of 6 observations per treatment.

2Least squares means and SEM were log2-backtransformed after the statistical analysis.